Dr M says: Can you believe it? #AdventBotany is now entering it’s 3rd year and is the festive botanical one to watch! Indeed it seems only yesterday Dr M was singing the Twelve days of botany and together with his colleague Dr Alastair Culham (@BotanyRNG) invented Advent Botany – 31 inspired nuggets of botanical peace, love and joy posted here and at Culham Research Group and dispersed across the Twittersphere to delight and inform – an inspired botanical Advent Calendar if there ever there was one and this year headed with another stunning botanical illustration by Niki Simpson (check her website here).

As last year Daughter of Advent Botany 2016 has been thrown open to the global botanical sisterhood and each day of Advent 2016 will iclude a botanical post by botanists of the world and announced via social media #AdventBotany! Scroll down for all previous posts.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 25: Botanical winter cheer from Erica x darleyensis

By Alastair Culham

It seems only right to devote the Christmas Day blog for Advent Botany to a plant that has brightened my winter garden for many years, Erica x darleyensis. This hybrid heath was first reported from a nursery in Darley Dale, Derbyshire in the late 1800s. It is a hybrid between the smaller winter heath, Erica carnea, another of my winter favourites, and Erica erigena, the Irish heath.

It seems only right to devote the Christmas Day blog for Advent Botany to a plant that has brightened my winter garden for many years, Erica x darleyensis. This hybrid heath was first reported from a nursery in Darley Dale, Derbyshire in the late 1800s. It is a hybrid between the smaller winter heath, Erica carnea, another of my winter favourites, and Erica erigena, the Irish heath.

Why do I love it so much? Firstly it flowers through the winter when the garden needs brightening, secondly it is one of the easiest heaths to grow and thirdly it offers a good range of colours from very greeny white through to deep rosy pinks. It needs little attention although it gains from pruning back every couple of years to keep it dense and vigorous.

Merry Christmas to all our #AdventBotany readers and you can find more on this lovely winter flowering plant here.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 24: #adventbotanists Vernon Heywood

By Dr M

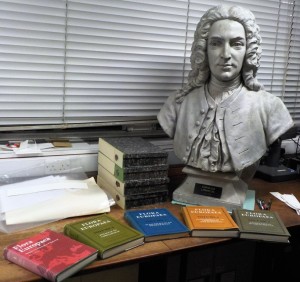

Dr M introduced to #adventbotany this year, #adventbotanists, botanists whose birthdays fall within advent. The first featured Erasmus Darwin a great botanical mind from a bygone age. Dr M’s second #adventbotanist features Vernon Heywood, born on 24th December 1927, widely recognised as a world authority on biodiversity and plant systematics, medicinal and aromatic plants, and the conservation of wild relatives of crop plants, and still very much active in his field.

Vernon Heywood was Professor of Botany and Head of Department at the University of Reading and in 1987 he left Reading (although still retaining the title Emeritus Professor of Botany) and became founder and director of Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) where his work very much emphasised the essential mission of botanic gardens as allowing people to connect with plants.

Vernon Heywood has published 60 books and 500 papers on plant taxonomy and systematics, medicinal plants, scanning electron microscopy, ecology, conservation, botanic gardens and plant genetic resources.

His publications include several major books including Principles of angiosperm taxonomy (1963), Flowering Plants of the World, and its update Flowering Plant Families of the World (with Richard K. Brummitt, Alastair Culham & Ole Seberg) as well as the Global Biodiversity Assessment.

One of his most celebrated and influential achievements was his involvement in the production of the ground-breaking flora of Europe entitled Flora Europaea. This is a 5-volume work published by Cambridge University Press. The aim was to describe all the plants of Europe in a single, authoritative publication providing keys and descriptions to aid the identification of any wild or widely cultivated plant in Europe to the species and where necessary sub-species level. It also provides information on geographical distribution and habitat preferences.

The Flora was released on CD-Rom in 2001, and the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh have made an index to the plant names available online.

The idea of a pan-European Flora was first mooted at the 8th International Congress of Botany in Paris in 1954. In 1957, Britain’s Science and Engineering Research Council (SERC) provided grants to fund a secretariat of three people, and Volume 1 was published in 1964. Further volumes were published in the following years, culminating in 1980 with the monocots of Volume 5. The royalties were put into a trust fund administered by the Linnean Society, which allowed funding for Dr John Akeroyd to continue work on the project. A revised Volume 1 was launched at the Linnean Society on 11 March 1993.

Throughout his illustrious career Vernon Heywood has been honoured with awards. In 1987 he was awarded the Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London. Planta Europa honoured him with their Linnaeus award at their 5th conference (2007). The book Taxonomy and Plant Conservation (edited by Etelka Leadlay & Stephen Jury, Cambridge University Press, 2006) was dedicated to Vernon Heywood

In a career spanning many decades, Vernon Heywood has worked and collaborated with many people and has engendered respect and admiration in equal measure. Here are just a few birthday salutations from colleagues past and present:

Gianniantonio Domina (Organization for the Phyto Taxonomic Investigation of the Mediterranean Area – OPTIMA): in these last 15 years I worked with Vernon and his wife Christine several times all over Europe. I have always appreciated his sense of humour and his love for travels, good food and good wine. But he is a very precise and thoughtful person.

Stephen Jury (previously Curator of RNG Herbarium, University of Reading): Vernon is still carrying out a punishing schedule in his 89th year and is still as sharp and witty as ever!”

Sue Mott (previously assistant curator of RNG Herbarium University of Reading):

In the early 1980’s I was a young technician in the then Plant Science Laboratories, working very much in Botany, and Vernon Heywood heard that I was considering buying a house (I was only 22) and he came to see me to tell me that his son worked in a local building society and that if I needed any help or advice on buying a house that I should contact his son. He gave me all the details and was very kind in his concern for my doing the right thing. It was very unusual for such a young, unattached, person to try to buy at that time. The care for those working under him or for whom he had any sort of responsibility was real and much appreciated and perhaps under reported in his case

Dr M: I joined the University of Reading in 2007 when Emeritus Professor Heywood was still teaching sustainable utilisation of plant resources on the MSc Plant Diversity and captivating his student audiences with stories of plants and people born from his wide travels and experience all over the world. It is my greatest pleasure to wish Vernon Heywood a very happy 90th birthday!

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 23: Vanilla

By Rachel Webster and Sophie Mogg

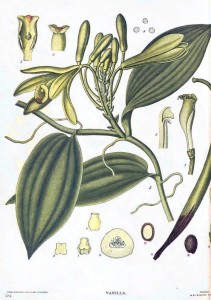

I’m not one for cream on my Christmas pudding, it just has to be custard or ice cream and so what I’m really admitting to is a love for vanilla. Vanilla is the quietest spice at Christmas but there is so much more to vanilla than merely two scoops of ice cream.

I’m not one for cream on my Christmas pudding, it just has to be custard or ice cream and so what I’m really admitting to is a love for vanilla. Vanilla is the quietest spice at Christmas but there is so much more to vanilla than merely two scoops of ice cream.

Natural vanilla is the fruit and seeds from a tropical, climbing orchid. There are other edible orchids (e.g. Dendrobium flowers and salep tubers), but it is certainly the most commonly used in food preparation. Some orchids are harvested from the wild to eat (such as Orchis mascula and O. militaris for salep), but given the demand, luckily this isn’t true for vanilla. There are over 100 orchid species in the Vanilla genus, but the most commonly cultivated species is Vanilla planifolia (more commonly known as Madagascan or Bourbon vanilla).

V. planifolia is native to Central and South America, and was first domesticated by the Totonac people of east Mexico, who used it exclusively until Aztec conquerors demanded vanilla as a tribute.

Read the full blog at Herbology Manchester.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 22: Crataegus mexicana (Tejocote)

By Megan Lynch

Traditions are made by people. We do something at a certain time and then we repeat it when that time rolls around again. There are young traditions and old traditions, but the longer a tradition is around, the more it’s part of the culture and a holiday just doesn’t feel like a holiday without it. People eat certain foods, drink certain drinks, and enact certain rituals every year. Plants are parts of people’s traditions because plants are a natural part of where people come from. And when they emigrate, they often take those useful plants with them.

Traditions are made by people. We do something at a certain time and then we repeat it when that time rolls around again. There are young traditions and old traditions, but the longer a tradition is around, the more it’s part of the culture and a holiday just doesn’t feel like a holiday without it. People eat certain foods, drink certain drinks, and enact certain rituals every year. Plants are parts of people’s traditions because plants are a natural part of where people come from. And when they emigrate, they often take those useful plants with them.

Crataegus mexicana or tejocote, is one of the many native species of hawthorn in North America. It is native to dry highlands in southern Mexico. It varies from shrub-like to more tree-like in form, reaching up to around 6m in height. It can take a certain amount of frost as well as drought, which has made it popular for rootstock experimentation in parts of Mexico and the US that are prone to both. While the southern US has a tradition of usingCrataegus fruit to make mayhaw jelly,Crataegus mexicana fruit takes on an important holiday aspect in Mexico.

California grows a large percentage of the produce in the United States and as such has long been concerned with controlling plant-related items that come across its border for fear of invasive agricultural pests. Thus a crucial ingredient to Mexican and Mexican-American Christmas traditions became a forbidden fruit. It was feared imports of the fruit would harbor fruit flies and other pests so it was not legal to import it. The fruit of the tejocote is used in ponche – a heated fruit punch made of tejocote, guava, sugar cane, and spices. And it just didn’t feel like Christmas without it so people were willing to pay high prices for smuggled tejocote.

California grows a large percentage of the produce in the United States and as such has long been concerned with controlling plant-related items that come across its border for fear of invasive agricultural pests. Thus a crucial ingredient to Mexican and Mexican-American Christmas traditions became a forbidden fruit. It was feared imports of the fruit would harbor fruit flies and other pests so it was not legal to import it. The fruit of the tejocote is used in ponche – a heated fruit punch made of tejocote, guava, sugar cane, and spices. And it just didn’t feel like Christmas without it so people were willing to pay high prices for smuggled tejocote.

In recent years, Californian fruit explorers and researchers have argued that it’s not realistic to merely forbid imports of fruits, vegetables, herbs, seeds and nuts that are of cultural importance to California’s many ethnic minority communities. A more effective way of keeping out agricultural pests and diseases is to assure clean inspected sources of plant material to cut the market from under those who would illegally import them because when it comes to traditions, people will find a way.

The restricted supply of tejocote also made it attractive for US growers to fill that need if they had the right growing conditions and could legally get ahold of propagation material. It’s been about a decade since people in Southern California could find legal sources of tejocote in their local ethnic groceries. Tejocote can now be found in several supermarkets that cater to specialty produce and at prices that are roughly half what was charged for smuggled fruit. Navidad can be feliz again!

More images and sources here.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 21: Cornus mas, the cornelian cherry

By Sophie Mogg

More commonly known as the cornelian cherry, Cornus mas is a medium-large deciduous tree of the dogwood family. Linnaeus referred to this species as both Cornus mas and Cornus mascula, translating to “male” cornel in order to distinguish it from the “female” cornel, Cornus sanguinea. It is native to South Europe as well as many parts of South Western Asia.

More commonly known as the cornelian cherry, Cornus mas is a medium-large deciduous tree of the dogwood family. Linnaeus referred to this species as both Cornus mas and Cornus mascula, translating to “male” cornel in order to distinguish it from the “female” cornel, Cornus sanguinea. It is native to South Europe as well as many parts of South Western Asia.

Cornus mas has a cold-hardiness rating of zone 4-8 allowing it to be successfully introduced to countries outside of its native range such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden as well as across the UK. Typically used as an ornamental plant, it is a bright and cheerful tree amongst the cold greys of winter. During autumn the glossy green leaves turn purple and come winter the tree boasts beautifully bright yellow flowers. The flowers appear around February to March and are typically very small (5-10mm in diameter) however they provide an important food source and a habitat for pollinators and other insects during those winter months.

Cornus mas has a cold-hardiness rating of zone 4-8 allowing it to be successfully introduced to countries outside of its native range such as Norway, Denmark and Sweden as well as across the UK. Typically used as an ornamental plant, it is a bright and cheerful tree amongst the cold greys of winter. During autumn the glossy green leaves turn purple and come winter the tree boasts beautifully bright yellow flowers. The flowers appear around February to March and are typically very small (5-10mm in diameter) however they provide an important food source and a habitat for pollinators and other insects during those winter months.

Read more at Herbology Manchester

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 20: Virgin birth and hidden treasures: unwrapping some Christmas figs

By Katherine Preston & Jeanne Osnas

Figs reach their peak in summertime, growing fat enough to split their skins under the hot sun. It’s nearly impossible to keep up with a bountiful tree, and many a neglected fig is extravagantly abandoned to the beetles.

But here we are, halfway around the calendar in dark and cold December, and we feel grateful for the figs we managed to set aside to dry. Their concentrated sweetness is balanced by a complex spicy flavor that makes dried figs exactly the right ingredient for dark and dense holiday desserts. As we mark another turn of the annual cycle from profligate to provident, what better way to celebrate than with a flaming mound of figgy pudding? Well, except that the traditional holiday pudding contains no figs. More on that later, along with some old recipes. First, we’ll unwrap the fig itself to find out what’s inside.

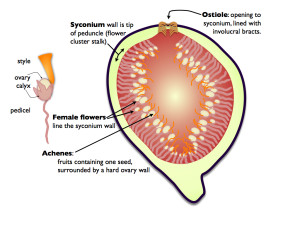

To understand a fig, you have to recall the basic structure of a flower and imagine the various ways flowers can be grouped on a plant. Figs (and related mulberries) cluster their tiny flowers together into dense and well-defined inflorescences. And, in both, all the flowers on an inflorescence develop into a single fused unit, which we casually call a fruit. Before offering the details of what we eat, we’ll need to look at the individual flowers and fruit.

To understand a fig, you have to recall the basic structure of a flower and imagine the various ways flowers can be grouped on a plant. Figs (and related mulberries) cluster their tiny flowers together into dense and well-defined inflorescences. And, in both, all the flowers on an inflorescence develop into a single fused unit, which we casually call a fruit. Before offering the details of what we eat, we’ll need to look at the individual flowers and fruit.

An idealized flower has four concentric rings of parts, or whorls. From the outside in, they are:

- usually green, modified leaves, called sepals (collectively the calyx), which are prominent in the nightshade family and on persimmons;

- petals, which are often colored or otherwise showy (together called the corolla);

- the “male” stamens, consisting of a filament holding aloft a pollen-filled anther; and

- one or more “female” pistils, anchored by an ovary. The pistil catches pollen grains, which then grow down through a style to the ovary and the seeds within. The ovary matures into a fruit.

Not all flowers have all of these parts. Figs make separate flowers with only one or the other sex: “female” flowers lack stamens and cannot make pollen, and “male” flowers lack pistils and cannot make fruit. Both female and male flowers also lack petals.

Fig flowers are a bit like Christmas presents: you can’t see them without opening up the structure that encloses them, and sometimes the wrapping is more exciting than what’s inside. As it turns out, being hidden from view also means being hidden from all but the most specialized pollinators, which is a big part of the fig story which you can read at the Botanist in the Kitchen blog.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 19: Christmas gourd

By Dawn Bazely

Prince Albert, who moved to England from Germany, to marry the young Queen Victoria, led the Victorians in inventing much of today’s Christmas aesthetic that dominates Britain and North America. But, the Nativity is celebrated by diverse cultures throughout the world, and is much more than, O Tannenbaum and The Holly and the Ivy.

Prince Albert, who moved to England from Germany, to marry the young Queen Victoria, led the Victorians in inventing much of today’s Christmas aesthetic that dominates Britain and North America. But, the Nativity is celebrated by diverse cultures throughout the world, and is much more than, O Tannenbaum and The Holly and the Ivy.

Many different local plants play important roles in Christmas traditions, and Alastair and Jonathan’s Advent Botany series has taught me a lot about them, along with the more traditional Middle Eastern, European, North American species that I regularly associate with my Christmas season.

Today, I’m inspired by the gift from a friend of a Peruvian fair trade ornament that is made from a hard gourd. The Cucurbitaceae or gourd family, includes important foods such as pumpkin, squash, melons and cucumber. Alastair’s yodelling gherkin from Day 1 of the 2016 Advent Botany series belongs to the this family, whose members were amongst the earliest plant species cultivated by humans.

Today, I’m inspired by the gift from a friend of a Peruvian fair trade ornament that is made from a hard gourd. The Cucurbitaceae or gourd family, includes important foods such as pumpkin, squash, melons and cucumber. Alastair’s yodelling gherkin from Day 1 of the 2016 Advent Botany series belongs to the this family, whose members were amongst the earliest plant species cultivated by humans.

While members of the gourd family are important food plants around the world, they play an especially important role in indigenous cultures of the Americas. The Wikipedia article on Cucurbita tells us:

“Along with maize and beans, squash has been depicted in the art work of the native peoples of the Americas for at least 2,000 years.”

When I looked into it, I discovered that my Christmas nativity ornament is not made from a squash or pumpkin gourd from the genus Cucurbita, but from the hardshell gourd, Lagenaria siceraria. These gourds have many uses, and Martha Stewart has a great video that shows how to turn them into vases and bowls.

Read more on Christmas and Gourds according to Dawn Bazely here.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 18: Madonna Lily

By Robbie Blackhall-Miles

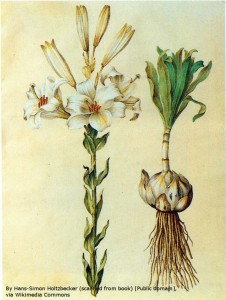

Not realising the hope they give me, through their winter rosettes of green, the bulbs of the Madonna lily (Lilium candidum) sit snugly in the soil year on year producing an ever-widening clump. Naturalised across Europe, and finding a happy home in the gardens of the UK, they hail from the Eastern end of the Mediterranean and still survive, albeit in a fragmented state, in the land to which they are most closely associated.

Not realising the hope they give me, through their winter rosettes of green, the bulbs of the Madonna lily (Lilium candidum) sit snugly in the soil year on year producing an ever-widening clump. Naturalised across Europe, and finding a happy home in the gardens of the UK, they hail from the Eastern end of the Mediterranean and still survive, albeit in a fragmented state, in the land to which they are most closely associated.

High up on Israel’s Carmel mountain, above the city of Haifa, the lilies are to be found in their crowded clumps fragmented and clinging on in crevices or protected from grazing animals, and the hands of wild bulb collectors, amongst the thorny Maquis vegetation dominated by Oaks (Quercus calliprinos – Fagaceae), Christ’s Thorn Jujube (Ziziphus spina-christi – Rhamnaceae) and Mastic (Pistacia sp. – Anacardiaceae). The Madonna Lily is now considered one of Israel’s most threatened species.

The mount on which they flower was a revered place for the early Jews in Israel and particularly for King Solomon. It features in the Old Testament Book ‘Song of Solomon’ with the line “your head crowns you like Mount Carmel” (Song of Solomon 7:5). The title of the book and the song took on King Solomon’s name due to his mention throughout the book. There is, however, evidence that the book was written by Solomon himself during the early part of his reign as king. The first line of the poem seems to state who wrote it ‘The song of songs, which is Solomon’s’ (Song of Solomon 1:1).

The mount on which they flower was a revered place for the early Jews in Israel and particularly for King Solomon. It features in the Old Testament Book ‘Song of Solomon’ with the line “your head crowns you like Mount Carmel” (Song of Solomon 7:5). The title of the book and the song took on King Solomon’s name due to his mention throughout the book. There is, however, evidence that the book was written by Solomon himself during the early part of his reign as king. The first line of the poem seems to state who wrote it ‘The song of songs, which is Solomon’s’ (Song of Solomon 1:1).

The links between Solomon and Lilium candidum are strong; the Bible describes the pillars of Solomon’s temple as having engravings of lilium candidum and the seal of Solomon (the Star of David) depicts a hexagram, a six-pointed star, the unification between masculine and feminine, the 6 petals of a lily. The song of Solomon describes an intimate love story; the interpretation of which has changed over time. In the 12th century the belief was that the bride mentioned in the song was Solomon’s prediction of the Virgin Mary and it is the line in this same song describing her that gives the lily its place at Christmas.

“I am a rose of Sharon, a lily of the valleys. As the lily among thorns, so is my love among the maidens (virgins).” (Song of Songs 2:2).

More on the Madonna lily and it’s Christmas connotations here.

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 17: A bright Christmas spikemoss – Selaginella

By Hans Olav Nymand

Denmark is a little land in Scandinavia, Northern Europe, but unlike the other Scandinavian countries, we have neither mountains (highest point 172m) nor vast boreal forests, and despite the relatively northern latitude, the Gulf Streams assure a cool temperate coastal climate with mild winters and cool summers.

Denmark is a little land in Scandinavia, Northern Europe, but unlike the other Scandinavian countries, we have neither mountains (highest point 172m) nor vast boreal forests, and despite the relatively northern latitude, the Gulf Streams assure a cool temperate coastal climate with mild winters and cool summers.

These geographic and climatic facts and a historical preference for intensive heavily mechanized agriculture, means that there are very few spots in Denmark with nutrient poor, undisturbed soils.

One consequence of this is that only one species of Selaginella can be found in the wild, S. selaginoides, the lesser clubmoss, and it is extremely rare, only small stands found only in a few protected areas.

One consequence of this is that only one species of Selaginella can be found in the wild, S. selaginoides, the lesser clubmoss, and it is extremely rare, only small stands found only in a few protected areas.

Now there are more than 700 species of Selaginella, where many are popular with terrarium enthusiasts, so you might think that some species would be available as houseplants – but mostly, they are not.

More on Selaginella here including some examples which are sold as advent botany plants in Denmark!

#AdventBotany 2016 – Day 16: Raphia a string for all seasons

By Yvette Harvey

Forget the gorgeous Madagascan bags, the baskets, the hats, the dates, the coconuts, the wine, the patterned mats and shoes, the most important product made from a palm has to be the string that holds the wrapping paper in place for your Christmas parcel. Remove from your mind visions of tropical beaches – our string is from a swamp loving plant, the Raphia.

Forget the gorgeous Madagascan bags, the baskets, the hats, the dates, the coconuts, the wine, the patterned mats and shoes, the most important product made from a palm has to be the string that holds the wrapping paper in place for your Christmas parcel. Remove from your mind visions of tropical beaches – our string is from a swamp loving plant, the Raphia.

The string is a fibre produced from the membrane on the underside of each individual frond leaf. There are c. 20 species of Raphia, mostly concentrated in West and Central Africa. Raphia are easily distinguished from other palms by their rather messy appearance as the leaves remain on the plant after death. They also have distinctive fruits that are covered in symmetrical rows of large, shiny, overlapping scales.

The carpological collection at the RHS herbarium (WSY) contains a fruit of Raphia taedigera, the Raphia that is said to be the source of Raffia fibre. This is the new world representative and the most widely dispersed of all the Raphia palms.

The carpological collection at the RHS herbarium (WSY) contains a fruit of Raphia taedigera, the Raphia that is said to be the source of Raffia fibre. This is the new world representative and the most widely dispersed of all the Raphia palms.

One of the less well known collections held by the RHS Lindley Library are the Nursery Catalogues. Along with a 1925 Nursery catalogue, we have an earlier sundries catalogue for H. Scott & Sons (London, England), and it can be seen that Raffia string is not a modern introduction to the UK. Alas, our Hipsters didn’t start the trend for Raffia string, it was clearly in use c. 100 years ago.

Read the full story of Raphia unwrapped here.

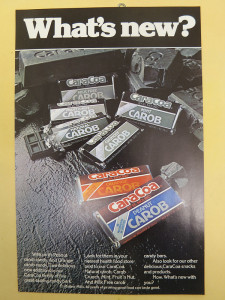

#AdventBotany Day 15: Carob Santa is on his way!

By Megan Lynch

At this time of year chocolate is imbibed as hot cocoa, eaten as a confection, pressed into the shape of Santa or snowmen, and baked into a variety of holiday treats from recipes often passed down within the family. But where does this leave you if you have an allergy or sensitivity to chocolate? Feeling a bit left out that’s where! There’s no real substitute for the flavour and “mouth-feel” of chocolate, but something with a similar flavour profile is carob. They both have coffee-esque notes but unlike chocolate, carob is sweet right off the tree and not very bitter. Like chocolate, carob can be used to make hot drinks, baked goods, and confections so it has been seen as “the next best thing” since health food speciality stores started taking off in the mid-20th century.

At this time of year chocolate is imbibed as hot cocoa, eaten as a confection, pressed into the shape of Santa or snowmen, and baked into a variety of holiday treats from recipes often passed down within the family. But where does this leave you if you have an allergy or sensitivity to chocolate? Feeling a bit left out that’s where! There’s no real substitute for the flavour and “mouth-feel” of chocolate, but something with a similar flavour profile is carob. They both have coffee-esque notes but unlike chocolate, carob is sweet right off the tree and not very bitter. Like chocolate, carob can be used to make hot drinks, baked goods, and confections so it has been seen as “the next best thing” since health food speciality stores started taking off in the mid-20th century.

Carob has such a long history as a cultivated plant that there’s still argument as to precisely where it originated. Regardless, it has a deep history in Eurasia, Mediterranean Europe and Africa. It is now also grown in other areas with a Mediterranean climate such as California, Australia, and South Africa. The pods can be eaten straight off the tree when ripe. The sugary flesh has a caramel-like taste to it. The varieties that have been selected over the centuries have ~ 50% sugar content. Carob also contains protein, calcium, phosphorus and fibre.

Carob has such a long history as a cultivated plant that there’s still argument as to precisely where it originated. Regardless, it has a deep history in Eurasia, Mediterranean Europe and Africa. It is now also grown in other areas with a Mediterranean climate such as California, Australia, and South Africa. The pods can be eaten straight off the tree when ripe. The sugary flesh has a caramel-like taste to it. The varieties that have been selected over the centuries have ~ 50% sugar content. Carob also contains protein, calcium, phosphorus and fibre.

Amazing botanical carob fact #1: Like cacao, carob is cauliflorous – that means it bears flowers directly from its trunk (also from its branches – a trait called ramiflory). Carob trees are dioecious (there are separate male and female trees) although only about 1% of carobs have perfect flowers. It has a bushy form that can be trained to grow as a beautiful hardwood tree of about 10m height.

Amazing botanical carob fact #1: Like cacao, carob is cauliflorous – that means it bears flowers directly from its trunk (also from its branches – a trait called ramiflory). Carob trees are dioecious (there are separate male and female trees) although only about 1% of carobs have perfect flowers. It has a bushy form that can be trained to grow as a beautiful hardwood tree of about 10m height.

Read more Carob-y Christmas-y facts here.

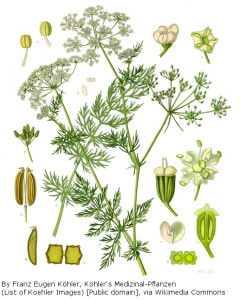

#AdventBotany Day 14: Getting carried away with Caraway!

By Emma (the unconventional gardener) Cooper

It’s possible to grow up in the UK and never consciously encounter caraway as a spice – I certainly did. And yet this versatile plant adds flavour to meat, fish, and vegetables details. But it’s claim to Christmas fame comes from its ability to make stand-out Christmas cookies, and wonderful cakes. As if that weren’t enough, it has magical powers to prevent theft, and stop geese from straying, and is a key ingredient in love potions. Sounds like caraway is a spice for life, and not just for Christmas!

It’s possible to grow up in the UK and never consciously encounter caraway as a spice – I certainly did. And yet this versatile plant adds flavour to meat, fish, and vegetables details. But it’s claim to Christmas fame comes from its ability to make stand-out Christmas cookies, and wonderful cakes. As if that weren’t enough, it has magical powers to prevent theft, and stop geese from straying, and is a key ingredient in love potions. Sounds like caraway is a spice for life, and not just for Christmas!

To really get carried away by Caraway read The Unconventional Gardener

#AdventBotany Day 13: A very festive Christmas with Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens)

Rachel Webster and Sophie Mogg

It’s always a joy to see something growing through these dark and dreary winter months. With glossy, green leaves, little cream bell-like flowers and big, red berries that start to appear as the snow melts, today’s plant, Gaultheria procumbens, is a very popular choice for baskets and containers. The name of this plant originates from Pehr Kalm, a Swedish explorer who named this plant after his good friend, Dr. Hugues Gaultier who expressed huge enthusiasm for the plants potential for tea.

It’s always a joy to see something growing through these dark and dreary winter months. With glossy, green leaves, little cream bell-like flowers and big, red berries that start to appear as the snow melts, today’s plant, Gaultheria procumbens, is a very popular choice for baskets and containers. The name of this plant originates from Pehr Kalm, a Swedish explorer who named this plant after his good friend, Dr. Hugues Gaultier who expressed huge enthusiasm for the plants potential for tea.

Read more at Herbology Manchester.

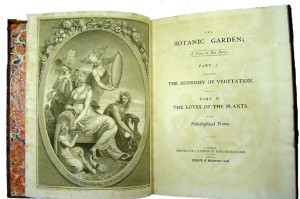

#AdventBotany Day 12: Erasmus Darwin born 12 December 1731 bringing botanical love and joy to the world!

By Dr M

Advent botany couldn’t be advent botany without botanists – and amongst them are a number of significant “advent botanists”, those born in the days of advent and Dr M’s first offering on this theme is Erasmus Darwin.

Born 12 December 1731, Erasmus is best known as grandfather of Charles Darwin. But Erasmus made significant scientific and other contributions in his own right as one of the key thinkers of the English Midlands Enlightenment (The Lunar Society), he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor and poet.

Born 12 December 1731, Erasmus is best known as grandfather of Charles Darwin. But Erasmus made significant scientific and other contributions in his own right as one of the key thinkers of the English Midlands Enlightenment (The Lunar Society), he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor and poet.

A larger-than life character in more ways than one, the life of Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) was quite the botanical soap opera, you really couldn’t make it up!

Amongst his numerous achievements:

- Married twice, had an in-between mistress, fourteen children and dozens of lifelong friends;

- Was asked by King George III to be his personal physician, but declined;

- Invented a shed-load of stuff including a speaking machine, a copying machine and the steering technique used in modern cars;

- Wrote The Loves of the Plants which includes vivid and highly sexualised poetry about reproduction in plants;

- Was passionate about the abolition of slavery, wrote a treatise on the education of girls and was friendly, generous, sociable and full of teasing humour;

- Paid little regard to authority and prescribed sex as a cure for hypochondria;

- Expounded a coherent theory of evolution of species from a common ancestor in a poem written in 1789;

- He enjoyed food so much he had a semi-circle cut out of his dining-table to accommodate his bulk!

His home in Lichfield, Erasmus Darwin House, is now a museum dedicated to his life’s work and well worth a visit.

Amongst his botanical achievements Darwin formed the Lichfield Botanical Society to translate the works of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus from Latin into English. This took seven years resulting in two publications: A System of Vegetables between 1783 and 1785, and The Families of Plants in 1787. In these volumes, Darwin coined many of the English names of plants that we use today.

Darwin then wrote The Loves of Plants a long poem, which was a popular rendering of Linnaeus’ works. Darwin also wrote Economy of Vegetation, and together the two were published as The Botanic Garden.

Darwin then wrote The Loves of Plants a long poem, which was a popular rendering of Linnaeus’ works. Darwin also wrote Economy of Vegetation, and together the two were published as The Botanic Garden.

Darwin’s final long poem, The Temple of Nature was published posthumously in 1803. The poem was originally titled The Origin of Society. It is considered his best poetic work. It centres on his own conception of evolution. The poem traces the progression of life from micro-organisms to civilised society. The poem contains a passage that describes the struggle for existence later made famous by grandson Charles Darwin in The Origin of Species.

Erasmus was not in the least coy about highlighting the sexuality of plants which had been long ignored or obscured by the language of more prim and proper Victorian scientists and authors. As Jenny Uglow puts it:

“The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus had revolutionised plant taxonomy. In his Systema Naturae he divided them into classes by the number of “male genitals”, the stamens (monandria, one stamen; diandria, two stamens), and then into orders by their pistils, the female “genitals”: the supporting structure, the calyx, became the “nuptial bed”. This meant, of course, that some flowers had far more than a single male – and the sexual naming went further, with some structures compared to labia minora and majora, let alone a whole class of flowers named Clitoria. There was no escaping the link between Linnaean botany and sex. His system was as accessible to schoolgirls as to scholars – and since botany was an accepted feminine subject, worried translators like Withering hunted feverishly for inoffensive English terms for the sexy Linnaean language, much to the scoffing of Darwin.”

So let’s leave the last botanical advent words to Erasmus pondering the glories of floral reproduction:

“ Hence on green leaves the sexual Pleasures dwell,

And Loves and Beauties crowd the blossom’s bell:

The wakeful Anther in his silken bed

O’er the pleased Stigma bows his waxen head;

With meeting lips and mingling smiles they sup

Ambrosial dewdrops from the nectar’d cup;

Or buoy’d in air the plumy Lover springs,

And seeks his panting Bride on Hymen-wings.

The Stamen-males, with appetencies just,

Produce a formative prolific dust;

With apt propensities, the Styles recluse

Secrete a formative prolific juice.

These in the Pericarp erewhile arrive,

Rush to each other, and embrace alive.

Form’d by new powers, progressive parts succeed,

Join in one whole, and swell into a seed.”

Further reading:

Desmond King-Hele Erasmus Darwin: a Life of Unequalled Achievement

Jenny Uglow: The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future, 1730-1810

Check out Dr M’s previous posting on Erasmus Darwin with lots of extra information and links here.

#AdventBotany Day 11 – The beauty of snowflakes microscopic algae

By Isabelle Charmentier

Ah, the snowflake: symbol of short winter days, crisp frosty mornings, Carol singing under the stars and the Christmas season.

Ah, the snowflake: symbol of short winter days, crisp frosty mornings, Carol singing under the stars and the Christmas season.

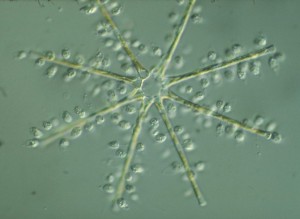

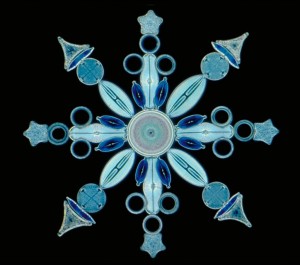

However, this is not a snowflake. It is a photograph of the mass development of the flagellate protozoan Bicosoeca on Asterionella. Asterionella is a genus of pennate freshwater diatoms, which are frequently found in star-shaped colonies of individuals, and therefore look remarkably like snowflakes. Diatoms are a major group of algae, and when we think of algae, we often think of seaweeds, algal blooms, and the slimy, slippery plants that render walking in a stream in our bare feet treacherous.

Algae can be quite beautiful, especially seen up close through a microscope. The Victorians certainly thought so and collected algae, pressed on herbarium sheets, and under slides. Victorian microscopists created artful arrangements of diatoms that were sold as miniature curiosities, beautiful patterns invisible to the naked eye that would come to life under a microscope. Today, Klaus Kemp is the only living practitioner of that singular art form, which displays nature in a structured and ordered way.

Algae can be quite beautiful, especially seen up close through a microscope. The Victorians certainly thought so and collected algae, pressed on herbarium sheets, and under slides. Victorian microscopists created artful arrangements of diatoms that were sold as miniature curiosities, beautiful patterns invisible to the naked eye that would come to life under a microscope. Today, Klaus Kemp is the only living practitioner of that singular art form, which displays nature in a structured and ordered way.

For lots more on these amazing organisms check here.

#AdventBotany Day 10 – Hoop-petticoat Daffodils

By Jordon Bilsborrow and Kálmán Könyves

Daffodils are very popular garden plants and an important commercial crop both as bulbs and as cut flowers. Our fascination with these very charming spring flowers has led to many cultural links in literature and art and there is evidence that these plants have been in cultivation for many centuries.

Daffodils are very popular garden plants and an important commercial crop both as bulbs and as cut flowers. Our fascination with these very charming spring flowers has led to many cultural links in literature and art and there is evidence that these plants have been in cultivation for many centuries.

Last year’s advent botany blogs featured Paperwhites (Narcissus papyraceus), a common daffodil available over the festive period. Paperwhites have to be specially prepared by artificial chilling to get them to flower for Christmas. This year we focus upon their less known, miniature cousins, hoop-petticoat daffodils which flower naturally through the winter season. This makes them an ideal Yuletide flower although they have not gained quite the popularity of the Christmas Rose, Winter Jasmine or other winter flowering garden plants common in British gardens, perhaps due to the preference for mild winters.

Narcissus section Bulbocodii are clearly distinguished from other daffodils by their large showy corona and rather reduced petals. Generally there are five species recognised in the wild; however two of these, N. romieuxii and N. cantabricus, are difficult to separate. They have a wide distribution ranging from southern France, throughout the Iberian Peninsula, to southern Morocco, and western Algeria. Taxonomically this group is problematic due to the abundant morphological variation, often within the same population, and prevalent hybridisation.

More on these lovely hoop-petticoats here.

#AdventBotany Day 9 – Getting stuffed at Christmas – The Onion

By Rachel Webster

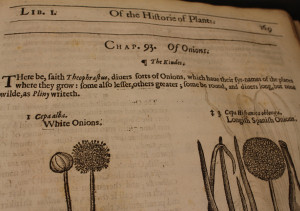

Not much of a surprise here, but after covering sage yesterday we really had to say a few words about onions today. If you want to be growing your own, then John Gerard’s Herball suggests that ‘The onion requireth a fat ground well diggedand dunged.’ However, as they are prone to rots and mildews, it might be better to go with some more modern horticultural advice in this instance! Gerard also reports that ‘it is cherished everie where in kitchen gardens…’ and that certainly hasn’t changed much since the 16th century. It’s fair to say that most of my cooking starts with an onion or two, despite the fact that I only have to look at one for it to make me cry.

Not much of a surprise here, but after covering sage yesterday we really had to say a few words about onions today. If you want to be growing your own, then John Gerard’s Herball suggests that ‘The onion requireth a fat ground well diggedand dunged.’ However, as they are prone to rots and mildews, it might be better to go with some more modern horticultural advice in this instance! Gerard also reports that ‘it is cherished everie where in kitchen gardens…’ and that certainly hasn’t changed much since the 16th century. It’s fair to say that most of my cooking starts with an onion or two, despite the fact that I only have to look at one for it to make me cry.

Chopping the onion up damages the cells and causes the release of enzymes and compounds that results in the production of the eye-irritating chemical with the catchy name syn-Propanethial S-oxide (try Scientific American for more detail). [Editor’s note: the popular chemistry blog Compound Interest also explains the chemistry of onion].

For much more on the Onion check here.

#AdventBotany Day 8 – Getting stuffed at Christmas – Sage

By Rachel Webster

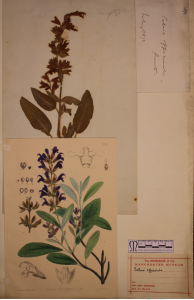

There are many more gastronomically interesting options available at Christmas time, but I’m still always drawn to the reassuringly traditional sage and onion stuffing. Nowadays, in addition to stuffing poultry, sage is often used to flavour other meat dishes (particularly sausages in British cuisine). However, its scientific name, Salvia officinalis, shows its heritage as a medicinal herb. The species name ‘officinalis’ comes from the Latin word officina meaning a monastic storeroom for herbs and medicines. Sage was recommended for all kinds of ills, from wounds and sore throats to hair care and fertility problems. There’s something about this suggestion from Gerard’s Herbal, however, which seems especially appropriate for overindulgent holidays:

There are many more gastronomically interesting options available at Christmas time, but I’m still always drawn to the reassuringly traditional sage and onion stuffing. Nowadays, in addition to stuffing poultry, sage is often used to flavour other meat dishes (particularly sausages in British cuisine). However, its scientific name, Salvia officinalis, shows its heritage as a medicinal herb. The species name ‘officinalis’ comes from the Latin word officina meaning a monastic storeroom for herbs and medicines. Sage was recommended for all kinds of ills, from wounds and sore throats to hair care and fertility problems. There’s something about this suggestion from Gerard’s Herbal, however, which seems especially appropriate for overindulgent holidays:

‘Sage is singular good for the head and braine, it quickeneth the sense and memory, strengtheneth the sinews….’ John Gerard, 1597.

Sage is in the mint family (Lamiacaeae). Many of the plants in this family are aromatic, but sage also shows some other very recognisable characteristics of the family such as a square stem, leaves in opposite pairs and flowers with bilateral symmetry with the five petals fused to give the appearance of an upper and a lower lip.

Much more on the botanical delights of Sage here.

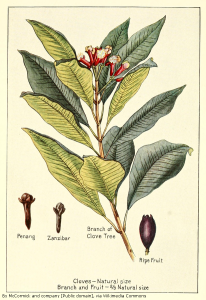

#AdventBotany Day 7 – The Clove

By Alastair Culham

To the microscopist, clove oil used to be one of the best smelling agents when preparing samples for permanent mounting on a glass slide. The corridor soon filled with the wonderful rich smell. However, cloves have a much wider range of uses including traditional use in herbal medicine to ease tooth-ache and to improve digestion. Cloves also make up part of the popular mixture with cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg, of winter spices to flavour cakes, puddings and such like.

To the microscopist, clove oil used to be one of the best smelling agents when preparing samples for permanent mounting on a glass slide. The corridor soon filled with the wonderful rich smell. However, cloves have a much wider range of uses including traditional use in herbal medicine to ease tooth-ache and to improve digestion. Cloves also make up part of the popular mixture with cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg, of winter spices to flavour cakes, puddings and such like.

Cloves are an unusual spice because they are dried flower buds while most spices are either fruit/seeds (nutmeg, star anise etc.) or vegetative parts such as stems (ginger, turmeric, cinnamon) and leaves (kaffir lime).

Syzygium aromaticum, the clove, is a member Myrtaceae, a family full of aromatic species from the common myrtle (Myrtus communis) to the largest broad-leaved trees in the world, Eucalyptus. It is native to Indonesia but is now cultivated in many parts of the tropics and has been in use, particularly in India and China for some 2000 years.

For more information and pictures check here.

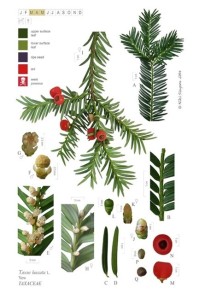

#AdventBotany Day 6 – Taxus baccata – the English or Common Yew

By Niki Simpson

The traditional Christmas tree here in the UK is the Norway spruce, Picea abies, while Abies nordmanniana is increasingly sold as the expensive “non-drop” Nordmann fir. However, mention must be made of our native yew, Taxus baccata, which can provide an alternative Christmas tree. Its tolerance of clipping (usually recognised in the form of ornamental hedging and topiary) also means that it can readily be pruned into a conical Christmas tree shape. But perhaps most of all at this time of year, yew is used with other festive foliage to make garlands, wreaths and all manner of home decorations.

Without a particular Yuletide association, yew is simply notable for its glossy green foliage at Christmas time, rather than for its flower or fruits. However, the yew fruits, on the female trees, are very striking, but take care, the seeds within the fleshy red aril, along with most parts of the plant are poisonous if ingested. The striking red fruits however rarely last until Christmas, generally being eaten by birds well before mid-winter. As an evergreen tree it provides welcome colour in the winter landscape and winter garden as well as much needed winter shelter to our fauna.

Without a particular Yuletide association, yew is simply notable for its glossy green foliage at Christmas time, rather than for its flower or fruits. However, the yew fruits, on the female trees, are very striking, but take care, the seeds within the fleshy red aril, along with most parts of the plant are poisonous if ingested. The striking red fruits however rarely last until Christmas, generally being eaten by birds well before mid-winter. As an evergreen tree it provides welcome colour in the winter landscape and winter garden as well as much needed winter shelter to our fauna.

Known in Britain as the English or Common Yew, it is native to Britain, but can be found across much of Europe, western Asia and North Africa. Although it does not bear typical cones, it is a conifer. Notably, it is one of only three British native conifers. It can found across the country, apart from the north of Scotland, favouring calcareous soils. Yews may be very long lived and ancient yew woodlands can be seen on the chalk of the North Downs and the Chilterns. Elsewhere yews are found as understorey in broadleaved woods, where they thrive in the shade.

Known in Britain as the English or Common Yew, it is native to Britain, but can be found across much of Europe, western Asia and North Africa. Although it does not bear typical cones, it is a conifer. Notably, it is one of only three British native conifers. It can found across the country, apart from the north of Scotland, favouring calcareous soils. Yews may be very long lived and ancient yew woodlands can be seen on the chalk of the North Downs and the Chilterns. Elsewhere yews are found as understorey in broadleaved woods, where they thrive in the shade.

Yew is familiar and recognisable to many of us, but not being as distinctive as the holly and ivy, it is a useful ‘background’ type of plant often taken for granted. We walk past yew without so much as a second glance. However conifers, including the yew, deserve closer scrutiny and appreciation. On first sight, conifer leaves all have a similar needle-like appearance but, when seen close to, are readily distinguishable from each other. The needle-shaped leaves are inserted spirally but appear to lie flattened in two ranks, one on either side of the shoot. The leaves point forward and are darker green above, more matt yellow-green below.

The yew is dioecious, with separate male and female flowers borne on separate trees. The pale flowers are carried on the lower surface of the twig of the previous year. The male flowers are larger than the female ones, but even those are inconspicuous and easily passed by. Like all conifers, the flowers are wind pollinated, but the ‘cones’ that develop on the female plant of the yew are not typical. Rather than bearing its seeds in a cone, each seed grows singly at the tip of a dwarf shoot, and becomes enclosed as it ripens, in a fleshy red aril up 1 cm long, but which remains open at the tip.

The yew is dioecious, with separate male and female flowers borne on separate trees. The pale flowers are carried on the lower surface of the twig of the previous year. The male flowers are larger than the female ones, but even those are inconspicuous and easily passed by. Like all conifers, the flowers are wind pollinated, but the ‘cones’ that develop on the female plant of the yew are not typical. Rather than bearing its seeds in a cone, each seed grows singly at the tip of a dwarf shoot, and becomes enclosed as it ripens, in a fleshy red aril up 1 cm long, but which remains open at the tip.

Editor’s note: Niki Simpson is a botanical illustrator interested in how botanical illustration can meet the needs of the 21st century botanist. Last year Niki provided the Yew banner for Son of Advent botany and this years banner (at the top of this post) is also one of her beautiful botanical creations. Check out her botanical selfie for Dr M here, and her website visual botany here

#AdventBotany Day 5 – Pōhutukawa!

By Alastair Culham

In Europe and North America, our Christmas trees are usually conifers. However, the New Zealand Christmas tree is a member of the Myrtaceae (Myrtle and Eucalyptus family). It is an evergreen tree of coastal North Island, New Zealand where it grows on cliffs and lava fields. The bright red flowers comprise brightly coloured stamens and rather small petals borne from November to January.

In Europe and North America, our Christmas trees are usually conifers. However, the New Zealand Christmas tree is a member of the Myrtaceae (Myrtle and Eucalyptus family). It is an evergreen tree of coastal North Island, New Zealand where it grows on cliffs and lava fields. The bright red flowers comprise brightly coloured stamens and rather small petals borne from November to January.

The species has the botanical name Metrosideros excelsa, and it is a very popular garden plant in mild temperate areas where it is represented in gardens by many different cultivars, some with white or yellow flowers.

The species is becoming rare in the wild and there is considerable effort to conserve this species due to its traditional role in Maori culture as well as it’s beauty and visual impact in coastal woodlands.

For more on this extraordinary plant check here.

#AdventBotany Day 4 – The Carrot!

By Alastair Culham

My dog’s got no nose. How does he smell? Awful. To prevent olfactory problems with snowmen the traditional nose of choice is the carrot.

To most westerners, the carrot is a bright orange tapering root vegetable that can be eaten raw or cooked and that forms a vital part of Christmas lunch. To the allotment gardener, there might be a wider choice including purple, yellow and white colours and a range of shapes from long and tapering to stump rooted or globular. The first time I tried growing purple carrots I remember thinking I had planted the wrong variety, however as the roots matured they went purple from the outside in. At first the roots were orange and then a purple colour developed late in the season giving a period of time when the carrots produced wonderfully colourful bicoloured purple/orange slices. Eventually the fully purple and wonderfully nutty flavoured carrots resulted.

To most westerners, the carrot is a bright orange tapering root vegetable that can be eaten raw or cooked and that forms a vital part of Christmas lunch. To the allotment gardener, there might be a wider choice including purple, yellow and white colours and a range of shapes from long and tapering to stump rooted or globular. The first time I tried growing purple carrots I remember thinking I had planted the wrong variety, however as the roots matured they went purple from the outside in. At first the roots were orange and then a purple colour developed late in the season giving a period of time when the carrots produced wonderfully colourful bicoloured purple/orange slices. Eventually the fully purple and wonderfully nutty flavoured carrots resulted.

This root vegetable is a native of the Euro-Mediterranean region and extending far into temperate Asia. Its origin dates back over 2000 years but is confused by the similarity between wild carrot (Daucus carota subsp. carota) and the edible carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) as well as other subspecies. This makes identification of archaeological material difficult. There is further confusion in historic illustrations where the parsnip and carrot are often indistinguishable.

This root vegetable is a native of the Euro-Mediterranean region and extending far into temperate Asia. Its origin dates back over 2000 years but is confused by the similarity between wild carrot (Daucus carota subsp. carota) and the edible carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) as well as other subspecies. This makes identification of archaeological material difficult. There is further confusion in historic illustrations where the parsnip and carrot are often indistinguishable.

For more information and weird carrot facts check here.

#AdventBotany Day 3 – A sweet surprise!

By Fi Young

Happy birthday to me, Happy birth… hold on just a minute this is the 25 days Advent Christmas Botanical Calendar, so why the birthday?

Happy birthday to me, Happy birth… hold on just a minute this is the 25 days Advent Christmas Botanical Calendar, so why the birthday?

My birthday does indeed fall on the 3rd day and like anyone else I do love a cake. But the cake for today is a Japanese Christmas Cake. However, Japanese do not celebrate Christmas so the 25/26 December is not a national public holiday but it doesn’t stop them celebrating or eating cake.

So move along you traditional Christmas cake ingredients cinnamon, nutmeg, cherries and sultanas, it’s time for the strawberry! The strawberry I hear you cry as you think hot summer days and Wimbledon Tennis! Yes, the strawberry!

This cake is lush. It can be any shape you want and is easily made. Make a light sponge, cover it with lashing of whipped cream and decorate with strawberries.

Fragaria x ananassa commonly known as the garden strawberry is an artificial hybrid between Fragaria virginiana Mill., the scarlet strawberry from Eastern North America and the walnut sized fruiting species Fragaria chiloensis (L.) Mill., the beach strawberry from Chile. The word for strawberry in Japanese is ichigo.

Descriptively the strawberry is not a berry at all, but an aggregated accessory fruit which consists of many small glabrous achenes embedded within the fleshy surface of the enlarged conical, fleshy red receptacle. An achene is a indehiscent dry fruit developed from a single ovule. Yeah the real annoying bits that get stuck between your teeth!

For read more about the strawberry and its special relationship with Japan here.

#AdventBotany Day 2 – How to create a Candy Cane Chrysanthemum

By Dawn Bazely

Peppermint candy canes are the North American equivalent of traditional British seaside rock. They are ubiquitous during the holiday season in Canada and the USA, showing up on Christmas trees, as stir sticks in hot chocolate, on doughnuts (below), and as decorations on gifts. They also appear in Biology classes as incentives provided by students to encourage fellow students to pay attention to their class presentations!

In recent years, a novelty flower, the Candy Cane Chrysanthemum, has appeared in my local florist. One turned up in a flower arrangement I received as a Christmas gift, a few years ago. I was intrigued by the green and red stripes running through the white flower, because they reminded me of one of my favourite childhood botany experiments. This is where you put a celery stick into water coloured with ink, and watch the xylem turn the colour of the ink? This was one of the things that inspired me to become a scientist, and a plant ecologist!

Check the full post here for all the details!

#AdventBotany Day 1 – Today I bought a yodeling gherkin on Ebay

By Alastair Culham

Advent botany enters its third year to the sound of a yodeling gherkin; but why?

It started with a list of the weirdest Christmas traditions in the Telegraph newspaper and resulted in me reading about a tradition that does not seem to be traditional or to have any kind of agreed origin – a wonderful apocrypha.

It’s all because of a disputed story about a pickle on a Christmas tree. There seem to be three competing origins for the Christmas pickle: (1) It’s an old German tradition; (2) it arose in the American Civil War and (3) it’s a medieval story about two Spanish boys trapped in a barrel and saved by St Nicholas!

Intrigued? Read (yodel?) all about it here!