Dr M and his University of Reading colleague Dr Alastair Culham (@BotanyRNG) have devised a seasonal botanical foray for your delight and delectation which has now been Twitterised as #AdventBotany.

There’s no chocolate goodie behind the little cardboard door, no cheeky Christmas cartoon characters, no snow-laden Christmas scene, just pure, simple and unadulterated #AdventBotany!

#AdventBotany Day 25 – to complete this landmark botanical Advent calendar the Star of Bethlehem is surely most appropriate to wish a Merry Christmas to all!

Dr M’s colleague Alastair Culham has prepared a typically informative and left of field post on the Star of Bethlehem from GOD for this Christmas Day, it is and it is not what you might expect! Read all about it at Culham Research Group here.

#AdventBotany Day 24 – The Brussel Sprout (Brassica oleracea var. gemmifera) is the true plant of Christmas! So says Professor John Warren, and he has statistics to prove his point! The British have a strange love-hate relationship with the Brussel sprout, purchasing 150 million of them during the week before Christmas and then boiling them to an inedible mush!

But 150 million is impressive and way more than we buy Christmas trees, which surely takes the humble sprout to the top Christmas botanical spot ousting the usual suspects – holly, ivy, mistletoe, Norway spruce and even frankincense or myrrh!

The botany of the Brussel sprout is remarkable, being merely a variety of the common cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and so is genetically the same as the cabbage but also to a wide range of other brassicas – cauliflower, broccoli, calabrese, kohlrabi, collards and kale.

The cabbage has been around for millennia – earliest records of cultivated cabbages are to be found in the writings of ancient Greece and Rome and date from around 600 BC, but in contrast, the sprout is a recent invention. It was first recorded in Belgium in 1750, near Brussels (well, it’s what it says on the tin!). From there it took about 50 years for the crop to spread to France and Britain.

OK so much for sprout botany what about sprout bottomy?

In greenhouse gas terms 150 million sprouts is massive and surely not to be sniffed at. But why does the sprout cause such silent but deadly, or not so silent but equally deadly, Christmas nights?

Well it all comes down to botanical weapons of mass destruction in the form of sulphur-containing compounds that sprouts, and indeed all brassicas (they’re all the same after all!), contain in their chemical arsenal to deter animals (including humans) from eating their leaves!

The problem is compounded since human bodies are not equipped with the enzymes to break down some of these compounds. One of these is the complex sugar raffinose which therefore passes unchanged from the small to the large intestine. Here it meets the microbes with the ability to break it down into odourless gases such as hydrogen and methane, but also other gases with added sulphur-pungency, such as the “bad egg” gas hydrogen sulphide and the “rotten cabbage” gas methyl mercaptan, both of these gases with a deadly pungency capable of filling and clearing rooms (and beds) in seconds!

The Brussel sprout, on the one hand such a humble plant, yet on the other, a botanically and culinarily intriguing, ultimately amusing and all-round botanical Christmas winner!

#AdventBotany Day 23 – Poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima) a modern house plant of Christmas if ever there was one! If you didn’t know you can tell its Spurge family – Euphorbiaceae – from the copious streaming white latex which exudes from any broken or damaged parts! Today’s blog is once again provided by Dawn Bazely who has experience of poinsettia as both a house plant and a garden plant. Poinsettias are native to Mexico and Central America, where they have been associated with Christmas since European missionaries colonized the Americas in the 17th century. They are the top-selling potted plant Canada and USA. What most people think of as the red flower petals, are actually bracts, which are modified leaves, the actual flower is tiny. Read more at Culham Research group here.

#AdventBotany Day 22 – A partridge in a pear tree is the first verse of the Christmas song “The Twelve Days of Christmas“. This is “cumulative song” each verse building on the previous one as a series of increasingly grand gifts is bestowed on the loved one from the first day – Christmas Day (or in some traditions, Boxing Day or St. Stephen’s Day) to the twelfth – the day before Epiphany, January 6.

The song, first published in England in 1780 as a chant or rhyme, is probably of French origin, indeed it is possible that the single botanical element, the Pear tree (Pyrus communis – Rosaceae), which appears only in the English version, could also indicate a French origin as perdrix (Old French pertriz) carried into the English version.

The verses add a new gift and repeating all the earlier gifts, so that each verse is one line longer than its predecessor:

1 A Partridge in a Pear tree

2 Turtle Doves

3 French hens

4 Calling birds (Colly birds)

5 Gold Rings

6 Geese a laying

7 Swans-a-Swimming

8 Maids-a-Milking

9 Ladies Dancing

10 Lords-a-Leaping

11 Pipers Piping

12 Drummers Drumming

There are many versions and accompanying tunes, but the familiar one is from a 1909 arrangement of a traditional folk melody by English composer Frederic Austin.

The origins and meaning of the song are obscure but it’s likely to have been a children’s memory and forfeit game. The best known English version was first printed in English in 1780 in a children’s book entitled “Mirth without Mischief”, as a Twelfth Night “memories-and-forfeits” game, where the leader recited a verse, each of the players repeated the verse, the leader added another verse, and so on until one of the players made a mistake, with the player who erred having to pay a penalty, such as offering up a kiss or a sweet.

There seems likely to be no truth in the more recent suggestion that the lyrics were intended as a catechism song to help young Catholics learn their faith, e.g. with the “true love” referring to God, and the partridge in a pear tree to Jesus, and subsequent verses to the two Testaments, the three Theological Virtues, the Four Gospels etc.

Dr M is more than happy to enter the silly #AdventBotany season and to add three more inherently lunatic variants to the long history of this Christmas song:

Firstly with “A.Partridge in a Pear tree” Dr M has lodged Alan Partridge (A.Partridge esq.) into a splendidly floriferous Pyrus sylvestris. To the uninitiated, Alan Gordon Partridge is a fictional character portrayed by English comedian Steve Coogan as a parody of sports commentators and chat show hosts.

Secondly, Dr M’s most recent variant is “Twelve Days of Dr M“ a botanical take on the Twelve Days with words especially recomposed by his students and other botanists on Twitter and issued recently as a potential first botanical number 1 Christmas song!

Finally, Dr M can take no credit for this third variant the clever parody by John Julius Norwich entitled: “12 Days (A Correspondence)” in which the loving Edward actually delivers all these gifts to his true love, Emily. It starts sweetly enough when Emily receives, what she describes as an “enchanting, romantic, poetic present – that partridge, in that lovely little pear tree!” And is followed by the delivery of what seems like an endless stream of different types of birds, and then goes from bad to worse with the arrival of “a regiment of shameless hussies” cavorting, followed closely by ten disgusting old men prancing about (some “taking inexcusable liberties with the milkmaids”). It ultimately descends into insanity and an acrimonious law suit issued by the now utterly incensed and enraged Emily!

- A.Partridge in a pear tree

- 12 Days (A Correspondence)

#AdventBotany Day 21 – Dates (Phoenix dactylifera). For many Christmas would not be Christmas without dried dates! The biggest producer is Egypt. In Saudi Arabia there are more than 450 date cultivars and in Oman more than 200. Dates are traditionally eaten either fresh, dried or preserved in honey. Fresh dates are far less stickily sweet than dried ones but have a shorter season as they do not store well. Dried dates are available all year round and can be eaten as an accompaniment to strong coffee where the sweetness balances the bitterness of the coffee. Fresh dates are becoming more readily available in the UK now.

Read more on #AdventBotany Dates including the work of researchers at the University of Reading at Culham Research group.

#AdventBotany Day 20 – Christmas Box – No, not getting ahead of ourselves here with Christmas boxes of the cash kind, traditionally given to tradesmen on Boxing Day (as a thank you for their year’s service) nor even presents in gift-wrapped boxes traditionally exchanged on Christmas Day.

- Google Christmas box

- Google Christmas box tree

What we do have in mind is the evergreen shrub commonly known as the Christmas Box or Sweet Box, Sarcococca confusa. It is an evergreen shrub which flowers over the mid-winter months with a delightful fragrance. It is in the family Buxaceae and related to the better known Common Box (Buxus sempervirens) used in box hedging in formal gardens. It is monoecious, with both male and female flowers found on the same plant and apparently named confusa because the female flowers may have two or three stigmas, and the male flowers any number of stamens between one and four. Confused or not, it makes a wonderful hardy evergreen shrub for the garden.

Thanks to digital botanical illustrator Niki Simpson for this post, check out her botanical selfie at Dr M here.

#AdventBotany Day 19 – It’s getting quite close to Christmas Dinner so Dr M’s colleague Alastair Culham takes a closer look, sniff and taste at your parsnips. The parsnip is a classic Christmas dinner vegetable, usually eaten roasted alongside potatoes and carrots. The edible part is the taproot, and this contains high quantities of dietary fibre (which has given the vegetable an unfortunate reputation for causing flatulent after effects) but also develops a high sugar content after chilling for a period of several days hence the truth of the commonly heard assertion that parsnips are better after the frost has been at them. Parsnips are particularly good if roasted with a little honey for extra sweetness and some English mustard to give a little heat to get the flavours coming through. Parsnips are part of the Apiaceae, the same family as carrots and celery, but also the same family as Hemlock.

More on parsnips – including Guinness world records for the biggest and longest – at Culham Research group.

#AdventBotany Day 18 – Amaryllis (Hippeastrum spp.). Thanks to Professor Dawn Bazely (York University, Toronto, Canada) for initiating this post (Dawn was last seen on #AdventBotany Day 9 Dogwood) and she writes:

“I was surprised to discover from a 2007 Daily Telegraph column, that Amaryllis is the most popular Christmas cut-flower in the UK. Who knew?”

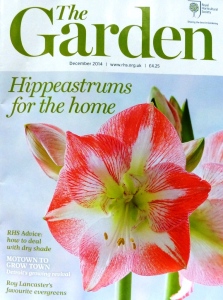

Dr M adds: Certainly the RHS is on to this, as shown by this front cover from the December issue of “The Garden“.

Dawn continues: “In Canada, Amaryllis bulbs are popular potted plants at Christmas, and everyone who gets one can usually keep it alive for a year. When my re-blooming Amaryllis flowers flop over, I cut them off and add them to arrangements.”

“But what we commonly refer to as Amaryllis is actually a common name for Hippeastrum species in the family Amaryllidaceae, native to South America, particularly Brazil. There are about 90 species and 600 hybrids of Hippeastrum.

“However, Hippeastrum is a quite distinct genus from the true Amaryllis, also in the same family, but native to South Africa.”

“The two genera are not dissimilar to look at, but using the common name of Amaryllis for Hippeastrum bulbs, rather than Amaryllis bulbs, is very confusing! But it is due to the equally confusing history of efforts to disentangle exactly how the different genera are related to each other!”

Dr M adds the taxonomic story in brief: In 1753 Linnaeus created the name Amaryllis belladonna, the type species of the genus Amaryllis. At that time both South African and South American plants were placed in the same genus, only much more recently being separated into two different genera.

The key taxonomic question is whether Linnaeus’s type species was a South African or a South American plant. The taxonomic debate culminated in a decision by the 14th International Botanical Congress in 1987 that Amaryllis should be a conserved name (i.e. correct regardless of priority) and ultimately based on a specimen of the South African Amaryllis belladonna from the George Clifford Herbarium at the British Museum (see Meerow et al. 1997). This decision settled the scientific name of the genus but the common name “amaryllis” continues to be used for Hippeastrum.

- Hippeastrum reginae (Source: Wiki)

- Amaryllis belladonna (Source: Wiki)

For more on Hippeastrum check Culham Research Group

#AdventBotany Day 17 – Different varieties of grapes Vitis vinifera (Vitaceae) have been dried to make raisins, saltanas and currants for thousands of years and they now form the basis of the familiar festive culinary accessories like the Christmas Cake, Christmas Pudding and sweet mincemeat for mince pies. These are all based heavily on dried grapes but with additional flavourings of spices, citrus fruits and almonds. but why do raisins, sultanas and currants have those names? Check Dr M’s colleague Culham Research Group for much more on these delicious preserved fruits.

#AdventBotany Day 16 – At the top of this post Dr M said there was no chocolate goody in Advent Botany, well this is not quite true for Lo! Here it is!

Surely, no series of Advent Botany would, could or should be complete without the divine chocolate!

Linnaeus named the cocoa tree Theobroma Cacao which literally means “Food of the Gods” reflecting the truly reverential status of the tree. The cocoa tree is a small tree, not unlike an apple tree in size, and is native to the tropical Amazonian forests. Over 3,500 years ago the Olmecs of Mexico were the first civilisation to use cocoa beans widely. They roasted and ground the beans, mixed in vanilla, chilli and spices to make a cold, bitter, savoury drink. The powers imbued by chocolate were thought to include spiritual wisdom, physical stamina and enhanced sexual prowess, what’s not to love about it?

Later it was discovered that judicious use of sugars could turn this bitter gruel into such a sweet devine delight that inevitably choco-mania spread throughout Europe. Plantations were established in other equatorial countries and West Africa is now the centre of world cocoa cultivation producing 70% of the world’s cocoa with four major cocoa producers – Ivory Coast, Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon.

Chocolate is made from a fruit – the cocoa bean – and around 50 almond-sized cocoa beans are contained within a cocoa pod, enough to make about eight bars of milk chocolate or four bars of dark chocolate. No doubt due to generations of inbreeding Cocoa is very prone to diseases and scientific research into disease resistance is a key element of the International Cocoa Quarantine Centre based at the University of Reading.

Britain really is a nation of chocolate lovers consuming 11kg per person per year on average – about 3 chocolate bars a week. The UK chocolate industry is worth more than £4billion and sales of chocolate (most recently in dark chocolate products) just keep growing and growing. Several of the big names in chocolate today – Cadburys, Fry’s, Terry’s, Rowntree’s – were founded by Quaker families keen for chocolate to take the place of alcohol the consumption of which they viewed as a major sin, whereas chocolate was just a minor vice!

Chocoholism is a completely explicable natural human response if we consider our Stone Age roots, when energy rich (fat and sugar) foodstuffs would have highly prized survival-linked value! Today we hardly need chocolate to survive and it’s omniwestern culture excessive consumption contributes to obesity, but in moderation there are benefits. Chocolate contains over 300 chemicals including vitamins and minerals, even the smell of chocolate can induce relaxation and a cup of pure cocoa has double the amount of antioxidants as green tea. Chocolate contains phenylethylamine which is released naturally in the body when ardour is inflamed, it also contains dopamine – a natural painkiller – and serotonin which produces feelings of pleasure. With over 400 distinct smells (a rose has just fourteen) no wonder chocolate was and still is considered the divine aphrodisiac! As the following tasteful 2012 “hit” song from Greece shows.

Want more chocolate?

Well, for a good comforting chocolaty read (even more tasteful than the Greek Eurovision entry) check Professor John Warren’s post on divine chocolate and discover why chocolate is the substance of choice for the top suppository manufacturers, get some amazing insights into the sex lives of the chocolate plant and find out exactly how many beans might be needed to secure the services of a lady of the night (in Mayan society at least!).

Also lots more yummy chocolate facts and figures from divinechocolate.com here

#AdventBotany Day 15 – The Christmas tree! But how did Christmas trees get to England? Dr M’s research suggests not via Prince Albert as often stated, but from good Queen Charlotte, German wife of George III, who reputedly displayed the first English tree at Windsor in 1800.

This year, for the first time, the University of Reading has an illuminated Christmas tree outside on the Whiteknights campus, it is a young Cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) now about 10m tall and showing the distinctive triangular shape of most young conifers. By far the commonest Christmas Tree in the UK is the Norway Spruce (Picea abies), including the traditional Norwegian gifted tree in Trafalgar Square, but almost twenty different species of conifer are regularly used as Christmas trees and you can read all about it from Dr M’s colleague at the Culham Research Group here.

#AdventBotany Day 14 – Day 13 we wrapped our Advent Botany Christmas parcels in botanical paper, Day 14 we tie them up with string! Modern Christmas string is most likely made from nylon, rayon, polyester or other synthetics. But how nice to deliver your Christmas parcels tied up with botanical string? String can be fashioned from the plant fibres of a wide range of species including:

Coir Coconut fibre (Cocos nucifera – Arecaceae)

Cotton (Gossypium – Malvaceae).

Flax (Linumusititissimum – Linaceae)

Hemp (Cannabis sativa – Cannabaceae

Jute (Corchorus sp. – Sparmanniaceae).

Nettles (Urtica dioica – Urticaceae)

Raffia (Raphia palm – Arecaceae).

Sisal (Agave sisalana – Plantaginaceae).

Imagine the joy, while researching #AdventBotany, Dr M was delighted to discover a secret stash of botanical strings and ropes fashioned from Cannabis sativa and others in the economic botany cupboard at the University or Reading, some images below:

If you fancy trying your hand at fashioning some hand-crafted string this Christmas, check out this video on making hemp string, highly therapeutic it seems, and if all else fails you can always smoke it, well you never know?!

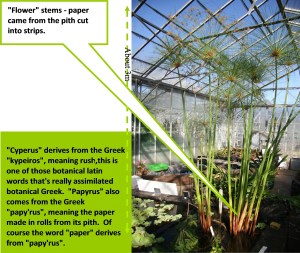

#AdventBotany Day 13 – Simple yet versatile, paper is a miracle of the plant world. Produced by the simple process of pressing together moist fibres, typically cellulose pulp, derived from the plant-based materials wood, rags or grasses and drying them into flexible sheets. Paper has an unrivalled versatility of uses – writing, drawing and painting, books, stationary and cards, boxes picture frames, wallpaper, screens, blinds and lampshades. Through papier-mâché and related compounds paper can be moulded into almost anything, including vases, trays, jewellery and furniture.

At Christmas time wrapping paper is a major preoccupation and Christmas without wrapping paper is unthinkable – in the UK more paper is consumed in this season than any other time of the year – in fact enough wrapping paper to go round the equator nine times, that’s a lot of paper!

The pulp papermaking process probably originated in China during the early 2nd century AD, by the Han court Eunuch Cai Lun. This early start has given rise to the modern pulp and paper industry and it is still China that leads production followed by the United States. The word “paper” comes from Papyrus, and the Egyptians, and later the Romans and others, pressed strips of pith from the flower stems together and dried them. No glue was needed, because the plant’s sap and some Nile water did the job. Papyrus isn’t as robust or flexible as paper made from fibre, so once the Chinese had used a Mulberry to make the first fibre-based papers in AD 105, its days were numbered. You can read lots more about papyrus in Dr M’s student Peter Rooney’s double tropical botany blog and fancy here.

But the last word on paper for today comes from Mark Miodownik Professor of Materials and Society at University College London. In his amazing book “Stuff Matters” he rhapsodises about how wrapping paper gives a Christmas gift “a crispness and pristineness that emphasise the newness and value” of the contents. The paper has mechanical properties that lend it to folding and creasing without falling apart, and yet allow it to be torn easily. It is “strong enough to protect the present during transportation but so weak that even a baby can rip it open.”

Paper: it’s a Christmas wrap!

Read more on paper here: The fascinating story of the Rice-paper plant (nothing to do with rice by the way!) and The history of paper.

#AdventBotany Day 12 – Gingerbread is a sweet biscuit or cake flavoured, unsurprisingly, with ginger (Zingiber officinale, Zingiberaceae) and other spices and sweetened with honey or molasses for sweetening. Gingerbreads range from a soft, moist loaf cake to something like a ginger biscuit. For example, Parkin is a form of soft gingerbread cake made with oatmeal and treacle which is popular in northern England.Gingerbread has a long history in Europe probably arriving in 992 by the Armenian Monk Gregory Makar. By the 18th century the town of Market Drayton in Shropshire, England had become famous for its gingerbread. The gingerbread man is the commonest type of gingerbread biscuit and first attributed to Queen Elizabeth I, who dished it out to her foreign guests. Today, however, gingerbread men are particularly associated with Christmas.

Almost every European country has its own variation on the gingerbread theme. In Germany gingerbread is made in two forms: a soft form called Lebkuchen and a harder form, particularly associated with carnivals and Christmas markets. The hard gingerbread is made in decorative shapes, which are then further decorated with sweets and icing.

Here are some lovely botanical gingerbreads especially commissioned for this post, now that’s yummy!

For hot, spicy take on Ginger spice check the Culham Research Group here

Here’s a December Graduation gingerbread man lovingly crafted by Dr M’s student Saba, and then carelessly broken by Dr M on the way home last night!

#AdventBotany Day 11 – Christmas rose (Helleborus niger). Many years ago in a far off land (probably about 2014 or so years ago and in Bethlehem to be more precise) there was a little girl called Madelon who had no gift to offer the little baby Jesus. She set out into the countryside to find a gift but could find none. Such was her grief, that tears sprung from her eyes, and as they hit the ground a beautiful white flower sprouted forth, the perfect gift of innocence and beauty for the little Christ child. This was the Christmas Rose.

This handsome herbaceous perennial is native to the Balkans but widely planted in gardens in Britain for its winter flowers. In fact it can already be seen flowering in some gardens this year – enough to justify the common name “Christmas Rose” (although it is in the family Ranunculaceae and nowhere near Rosaceae!). However Madelon’s story is more apt as in some years the Christmas Rose flowers even later than the Lenten Rose (Helleborus orientalis).

Furthermore, being in the family Ranunculaceae, the flowers are not always exactly what they seem! And so what appears at first sight to be white petals are in fact persistent sepals (technically tepals, since there are no distinct sepals and petals).

The scientific name Helleborus comes from the Greek “elein” meaning to injure and “bora” meaning food and many species are poisonous.

The illustration is from www.albion-prints.com and is an Antique Copper Plate Engraving published 1787-1800 by William Curtis, London for “The Botanical Magazine”.

If, like Dr M, you love this plant, check out the species and numerous hybrids and varieties at the National Collection of Helleborus here.

#AdventBotany Day 10 – One of Dr M’s favourites, but just how many plant species are there is the perfect festive Mulled Wine?

Now so often a hectic, cloying, syrupy brew served at Christmas markets or a quick and dirty way of disposing of a bottle of cheap red plonk, take a moment to remember that mulled wine was in the past a symbol of wealth and status and imbued with medicinal and even aphrodisiac properties, no doubt due to its ability to warm the very cockles.

“Mulled” means to warm and add spices and spiced wine dates back more than 5000 years to ancient Egypt and was probably laced with a number of plants that we would not expect in mulled modern mulled such as pine resin, figs, and the herbs balm, coriander, mint, and sage. Mulled wine was widespread in the Roman Empire and hot spiced wine became a staple in many parts of Europe and the Middle East, especially to help through the long winter months. The crusades then played its part disseminating the spice-infused nectar far and wide with recipes now including more familiar ingredients such as cinnamon, ginger and cloves. Mulled wine sweetened with sugar rather than honey became a symbol of rank – “sugar for the Lords and honey for the people”. How times change!

England invented varieties such as Wassail (the traditional Christmas song “Here we come a Wassailing…” composed ca. 1850) and classic Mulled wine. In Victorian England Negus was usually made with a sweet wine, water, lemon peel, lemon juice and nutmeg. Many other European countries began to form their own interpretations of spiced wine to represent their cultural identities, the two most well-known probably being Spanish Sangria – cold spiced wine with cinnamon, ginger, and pepper and German (and Austrian) Glühwein, literally “glow-wine” due to the hot irons once used for mulling (and perhaps the cockle-warming impact too?). Less well known are the Nordic Gløgg, made with raisins and almonds, and the Polish wine soup in which cream is added to mulled wine, making a rather classy breakfast!

If this has all rather whetted your appetite for some decent mulled wine try the Guardian recipe purporting to be “the perfect mulled wine recipe” containing the following perfect nine botanicals in seven different families:

Lauraceae – Cinnamomum spp. – Cinnamon

Myristicaceae – Myristica fragrans – Nutmeg

Myrtaceae – Syzygium aromaticum – Cloves

Poaceae – Saccharum officinarum – Sugar cane

Rutaceae – Citrus × limon – Lemon

Rutaceae – Citrus × sinensis – Orange

Vitaceae – Vitis vinifera – Red wine (Grapes)

Zingiberaceae – Elettaria cardamomum – Cardamom

Zingiberaceae – Zingiber officinale – Ginger

Find the Guardian recipe here, and yet more mulled winery going on at Spicy Vines.

For a very spicy take on mulled wine check Dr M’s colleague at Culham Research Group here.

Cheers!

#AdventBotany Day 9 takes a long haul-flight to north America to the home of Dawn Bazely (Professor of Biology at York University, Toronto) to find the lovely red-stemmed Red-osier Dogwood (Cornus sericea). Red is always a classic Christmas colour and add a splash or two of green and you are good to go! Dawn writes:

It is not surprising that the red stems of this native North American shrub are a staple element of Christmas and other seasonal decorations across the continent. Red-osier dogwood is common in damper areas of forests. Dawn’s local florist, Candice, told her how she would cut branches from bushes in ditches and woodlots for arrangements. As well as occurring naturally, Red-osier Dogwood has been cultivated and is a popular ornamental shrub in north America.

Some of the cultivars have variegated leaves, like the one growing in Dawn’s garden and Dr M also has this in his own garden in Reading, UK and will be trying his hand at making some festive arrangements himself!

Dr M adds: In addition to the recent adoption for festive decorative use, Cornus sericea has many traditional uses, e.g. Native Americans smoke the inner bark in tobacco mixtures used in the sacred pipe ceremony. The inner bark is used for tanning or drying animal hides. Dreamcatchers, originating with the Potawotami, are made with the stems of the sacred red osier dogwood. Some tribes ate the white, sour berries, while others used the branches for bow and arrow-making, stakes, or other tools.

Although native to N America, Cornus sericea is now widely naturalised in Britain and found in woodland and along riversides, sometimes suckering to produce extensive thickets; also much planted in parkland, amenity plantings and on roadsides and sometimes occurs as an escape on waste ground and marginal land. Check out the BSBI Atlas map here.

Reference: USDA NRCS Plant Guide Red-osier Dogwood

#AdventBotany Day 8 – Saucy or Juicy, there’s one helluva lot of Cranberries in Advent Botany!

If you are sharp-eyed enough to have seen the native European Cranberry fruiting, then you might have wondered how anyone ever found enough berries to turn them into the sharp red sauce that is now an essential part of many Christmas dinners. Vaccinium oxycoccus, the wild cranberry is a diminutive plant whose thread like stems grow through other vegetation in our acid bog-lands. With leaves that struggle to reach a few millimetres in length it always seems amazing that such a tiny plant can produce such large fruit. This could explain why cranberries are somewhat reluctant to fruit and most British botanists will tell you that they have not seen it produce more than a spoonful of fruit, let alone a jam jar full!

Today cranberry juice seems to be available everywhere in copious quantities and not just at Christmas. However, this is not the product of the European Cranberry but its rather more robust American relative Vaccinium macrocarpon (the clue is in the specific epithet, “macrocarpon” which literally means big fruits!). The American cranberry is a most remarkable crop, because although it’s hardly been domesticated from the wild, it has possibly the most high tech cultivation system of any modern crop.

- Vaccinium oxycoccus

- Christmas Vaccinum macrocarpon

- Harvesting Vaccinium macrocarpon

Thanks to Professor John Warren for this #AdventBotany post and read more from him and his great bouncing and floating Cranberries here!

Image credits: Cranberry images #1 and #3 and more information at Wikipendia here.

#AdventBotany Day 7 – did the almond tree grow from Agdistis’ severed genitals or was it created to honour Phyllis’ wait for Demophon? Almond, Prunus dulcis – a tree that provides both sweet and bitter nuts.

#AdventBotany Day 6 – staying in the Burseraceae, Commiphora myrrah or Myrrh is an anti-inflammatory, flavouring and scent but over use can lead to side effects. Used in ancient Egyptian embalming of mummies. Now used to keep skin looking young.

The Song of Solomon reports:

Who is this coming up from the wilderness

Like palm-trees of smoke,

Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense,

From every powder of the merchant?

Till the day doth break forth,

And the shadows have fled away,

I will get me unto the mountain of myrrh,

And unto the hill of frankincense.

In this photo, bark and resin of C. myrrah.

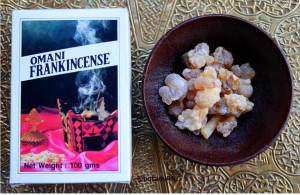

#AdventBotany Day 5 – resinous sap of Boswellia sacra (and other related species), from southern Arabia, called Arabia Felix for its providence in having such a valuable plant. Frankincense was arguably the fuel of the first global economy (ca. 500BC-500AD) and the ‘Land of Frankincense’ is now a World Heritage site (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1010). Famed in Christian cultures as the 2nd gift of the Magi to Christ.

#AdventBotany Day 4 – Gold!

Perhaps the most obvious plants to write about are the numerous species with gold (aurea and its forms) in their names. These range from Abrus aureus, a climbing vine in the pea family that is native only to Madagascar, to Zizia aurea or “Golden Alexander”, a yellow flowered member of the carrot family native to north America however this is not the most interesting story of gold to be reported by far.

Several plant species are able to accumulate metals, some in quite high concentrations by accumulation from the soil. This process is known as phytomining and can be the most cost effective way of concentrating low levels of heavy metals from soil. A major report by the US geological survey in 1968,Metal Absorption by Equisetum (Horsetail), suggested that reports of horsetail (Equisetum) accumulating high levels of gold from the environment were questionable although it did contain some gold.

Other plants have been shown to accumulate a range of metals including Gold, prominent among these are members of the cabbage family (Brassicaceae). Several members of Brassicaceae are known to accumulate heavy metals including lead as well as gold. Recently it has been shown that the gold is stored as nanoparticles in plant cells. The growing of metal accumulating plants on polluted soils and the subsequent accumulation of metals can be important in cleaning up these soils, so-called phytoremediation and phytoextraction.

So whether you want real gold from hyperaccumulators or are happy with gold coloured plants there is a range of species to cater for your needs.

#AdventBotany Day 3 – Ilex is the only genus in the family Aquifoliacaeae (The Hollies). In Europe we know Holly (Ilex aquifolium) which is the third of our Christmas evergreens alongside Ivy and Mistletoe. Holly was brought in to houses in pagan times to keep evil out but was then adopted by Christians as a representative of the crown of thorns at Christ’s crucifixion. However there are around 400 different holly species and many do not have prickly leaves. Ilex paraguariensis is used to make the infusion Mate, the caffeine rich national drink of Argentina. In contrast, Ilex crenata is grown in Japan, China and Korea as a small decorative shrub used in complex topiary displays. If you are interested there are specialist suppliers of Ilex crenata bonsai trees and, for example, if you want a 4 foot plant it’s a snip at £1150, taller specimens can reach £6000!

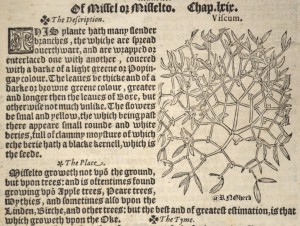

#AdventBotany Day 2 – Viscum album (Mistletoe) another evergreen, but this time more sinister. This hemi-parasitic plant grows on a range of broadleaved trees including apple, linden and oak. It has a long tradition in Druidic ritual and the Romans report the harvesting of the species from Quercus (oak) by Celtic Druids using a golden sickle. This poisonous plant contains the lectin viscumin which is similar to ricin.

From the 16th century mistletoe became associated with kissing in some Christian cultures. In the photo below you can see part of the entry on Viscum from Lyte’s ‘A niewe Herball’ published in 1578. This is the oldest book held by University of Reading Herbarium (RNG).

Find lots more about Mistletoe at Culham Research Group and at Jonathan’s (no relation!) Mistletoe Diary.

And for the real enthusiasts, check out the PhD thesis on the evolutionary ecology of European Mistletoe by Doris Kahle-Zuber here, I kid you not, the whole PhD is there!

#AdventBotany day 1 – Hedera helix (Common Ivy) whose highly variable evergreen leaves symbolize eternity and resurrection. Ivy has a distinctive waxy sheen to the upper surface of the leaf. It’s reputed to keep witches away if you grow it up a house wall. Long associated with mid-winter festivals including Christmas because it stays green even in this cold dark season. All leaves in this photo are from a single plant!

#AdventBotany – one-a-day Advent Botanical until the fat man comes down the chimney and eats all your snacks!

The Featured image is a Christmas collage by botanical artist Niki Simpson.